When it comes to European club football, some nations are bigger than others. Here’s a definitive look at the most successful Champions League nations, and the great teams, players and managers that lifted club football’s most prestigious trophy.

We know that the Champions League was called the European Cup before the early 90s, but for the sake of convenience we’ll call it by its current name.

So let’s start with the nations with the fewest wins and work our way up to the continent’s footballing superpowers.

In 92-93 the tournament had a short-lived group stage that actually kicked in after two knockout rounds.

It was the early days of the Champions League as we now know it, and in this time Marseille had a formidable team backed by their shady president Bernard Tapie, who would get the club relegated from Ligue 1 at the end of the season for match-fixing.

But in spring 1993 they were at the top of the European game, calling on present and future stars like Deschamps, Basile Boli, Desailly, Barthez, Alen Bokši?, Abedi Pele and Rudi Völler.

OM, managed by Raymond Goethals, got the better of Fabio Capello’s strong AC Milan side at the Olympic Stadium in Munich.

Boli got the only goal, a header, and Marseille held on to claim France’s only European title to date.

AC Milan would have to wait another season to lift the trophy, while Marseille’s success has been mostly forgotten because of the doubts that shroud Tapie’s time in charge of the club.

Take nothing away from Steaua Bucharest, but 1986 was an odd year in European football.

The game was still recovering from the Heysel Disaster at the 1985 final, which resulted in 39 deaths and saw English teams banned from continental tournaments for the next five years.

Steaua were coached by the wily Emerich Jenei, a tactical mastermind. And their stars on the pitch were the slippery forward Marius L?c?tu?, whose name is still chanted by the Steaua fans, and midfielder László Bölöni, who picked up more than 100 caps for his country.

Netting the goals was striker Victor Pi?urc?, scoring five times on the way to the final.

Tactically, Steaua were an attritional team, especially in the final when they clung on for extra time and then penalties against Terry Venables’ Barcelona.

L?c?tu? and Balint scored from the spot, Barcelona couldn’t convert a single one, and so Steaua made history.

Needless to say that Jock Stein’s 1967 Celtic team will be remembered forever by The Bhoys fans. Their final against Helenio Herrera’s Inter Milan in Lisbon was a real clash of footballing cultures.

Herrera was a specialist in Catenaccio, that ultra-defensive counter-attacking style. Stein’s men played with verve and freedom.

Stevie Chalmers got the goals, and the centre-forward had an inspired season that year, scoring in every round except the semis. But the imagination came from right-winger Jimmy Johnstone, famed for his quick feet and voted Celtic’s best ever player by their fans in 2002.

What’s remarkable about the final is that even though Inter scored first via Mazzola from the spot, Celtic were able to break through that stout Nerazzurri defence and claim their famous victory.

They did it with two long range strikes past Giuliano Sarti, first from left-back Tommy Gemmell from 25 yards.

Then, with five minutes on the clock Bobby Murdoch had a go from distance, and Chalmers’ penalty-box instincts allowed him to divert the ball home to achieve a victory no Scottish team has managed in the 50 years since.

In 1991 English clubs were back in Europe, but league champions Liverpool still had to sit out another year. None of this made much difference when you see the talent that Red Star Belgrade had at their disposal that season.

For the Serbian club it was a moment in history that can never be repeated, as it took place on the cusp of the Balkan wars, and the region would never be the same after.

The final was a drab, cagey match against Marseille in Bari, Italy. The coach Ljupko Petrovi? even told his players to get rid of the ball and worry about keeping their shape.

After 120 minutes of little action the match went to penalties and Red Star held their nerve, scoring all five from the spot to punish Manuel Amoros’ miss.

But you have to take a moment to appreciate the talent in that Belgrade side.

It was almost a Balkan dream team, made up of players from different parts of the former Yugoslavia, including Croatians, Montenegrins, Macedonians and Serbs, all playing for the same side.

Robert Prosine?ki, Siniša Mihajlovi?, Darko Pan?ev, Dejan Savi?evi? and Vladimir Jugovi? all made an impact in Europe’s big leagues in the coming years.

In the early 60s there was one team to beat in Europe: Béla Guttmann’s Benfica. They won the trophy in 1961 against Barcelona, and then retained their title in ‘62 when they beat Real Madrid.

The second final was famous for the performance of the 20-year-old Eusébio who took the game by storm and scored two in a 5-3 victory. Benfica appeared in three more finals that decade but couldn’t win again.

And that’s where it gets spooky. Béla Guttmann had left the club in ‘62 after his request for a pay rise was turned down, allegedly saying, “Not in a hundred years from now will Benfica ever be European champion”.

Benfica have played in eight Champions League and Europa League finals since then and lost in every one.

Benfica’s domestic rivals have had a bit more luck than that. Coach Artur Jorge led a depleted team to victory against Munich in 1987, in a 2-1 fightback after they had gone one down.

Munich were the superior side on paper, with Matthäus, Rummenigge and Brehme, but two delightful goals including a backheel by the skilful Algerian attacker Madjer sealed a surprise win.

Then in 2004 Porto’s streetwise team with Deco and Ricardo Carvalho and captained by Jorge Costa announced the arrival of Jose Mourinho as a world-class coaching talent.

If Benfica were the team of the early-60s then the early-70s belonged to Ajax. Their impact on football is still being felt today.

And for three years nobody could work out how to cope with the technical ability of players like Johan Cruyff, Johan Neeskens and Piet Keizer, as well as the tactical innovation of coach Rinus Michels’ Total Football.

This involved players switching positions and being responsible for zones, at a time when most teams favoured man-to-man marking. It made them impossible to defended against.

Before them, Feyenoord had won the cup in 1970. Their most recognisable player was the creative midfielder, Wim van Hanegem, who became a linchpin of the Dutch national team.

And you can talk about Guttman’s curse all you like, but when PSV beat Benfica in 1988 they had the basis of a Netherlands side that would also win the Euros that year.

Ronald Koeman and Gerald Vanenburg are two of the best footballers the country has produced, and helped PSV to a penalty shoot-out win.

Then, in 1995 Ajax took the football world by storm again, when van Gaal’s young team overcame Milan in Vienna. Seedorf, Kluivert, Rijkaard, Davids and the de Boer were just some of the names involved.

After Ajax’s time at the top came to an end, Bayern Munich took over, winning three titles between 1974 and 1976. They were a side that married great talent and tactical sense with an iron will.

But of course the main man was Franz Beckenbauer. If Cruyff had been essential for Total Football, Beckenbauer defined the Libero Role.

For the first time the central defender was the best player on the pitch, and Beckenbauer’s complete mastery of both defence and attack made them unbeatable.

Able support was offered by German legends like Breitner, Schwarzenbeck, Uli Hoeneß and the ultra-prolific striker, Gerd Müller.

In the late-70s and early-80s Hamburg were a serious European force, and their win in 1983 was the culmination of half a decade of domestic success.

The man in charge was the revered Ernst Happel, who had taken them on a 36-game winning streak that season. Horst Hrubesch and Felix Magath were the key players, and it was Magath that got the winning goal in a 1-0 victory against Juve.

Dortmund caused a stir in ‘97 when a very accomplished team with the Ballon d’Or holder Matthias Sammer doing a great Beckenbauer impression as sweeper, and Andy Möller pulling the creative strings further forward.

Bayern reemerged as a force to be reckoned with at the turn of this century. They suffered last-minute heartbreak against Man U in 1999, but bounced back to claim a win orchestrated by the volatile creator Steffen Effenberg.

There were more near misses in 2010 and 2013, but they found a new level under Jupp Heynckes, winning the Champions League as part of a treble. Neuer, Boateng, Lahm, Ribéry. Schweinsteiger and Thomas Müller were some of the protagonists.

And now we’re walking with giants. The mid to late-60s were all about the two Milan teams. First it was the turn of Helenio Herrera to bring man-marking and pragmatism to the fore, claiming two wins in ‘64 and ‘65.

But that isn’t to say that Inter had no creativity: Key to their counter-attacking style were highly-technical creative players like Sandro Mazzola and Luis Suárez.

Herrera’s side outfoxed everyone in the mid-60s and their success was bookended by AC Milan, who won it in ‘63 and ‘69.

The Rossoneri were also Catenaccio merchants under Nereo Rocco who invented this system. Their solid defence was founded on Roberto Rosato, a classically Italian ball-playing central defender. And the stylish midfielder Gianni Rivera was the man with the plan.

The Old Lady has won the big one twice, in 1985 and 1996 but has three times as many runners-up medals. When they won it in 1985 they had a tasty-looking attack with Paolo Rossi, Michel Platini and Zbigniew Boniek.

Trapattoni was the manager that time, and he had already won the cup twice as a player with AC Milan in the 60s. They tasted success again under Lippi, when a team crammed with experience got the better of that young Ajax side on penalties.

Deschamps, Ravanelli, Vialli, Vierchowod and Ciro Ferrara were some of the heroes of that night.

In the late-80s it was AC Milan that were running things. Arrigo Sacchi developed a new kind of football that was very un-Italian. Instead of caution he opted for a high-defensive line, zonal marking, a crazy offside trap and relentless attacking.

Nobody had an answer for it, and they swept all before them in 1989 and 1990. It helped of course that Baresi, Costacurta, Maldini, Rijkaard, Gullit and van Basten were all involved.

Milan’s was the last dynasty, as no club has managed to retain the Champions League since they did it in 1990. Wins also followed in ‘94 under Capello, and then again with Ancelotti in 2003 and 2007.

Present for both of these wins was a golden ensemble of footballers that included Gattuso, Maldini, Seedorf, Inzaghi and Pirlo.

Then in 2010, Mourinho steered another unfancied club to European triumph with Inter Milan against Bayern Munich.

Inter played cautious football, but were deadly on the break, especially with the pace of Samuel Eto’o and the striking instincts of Diego Milito. It was the Argentine forward who made the difference with two deft goals.

English sides never had a look-in on the European scene until the late-60s. Then the iconic United manager Matt Busby pulled off the stunning feat of winning the biggest trophy in club football a decade after the Munich Disaster had decimated the club.

Most of the stars of that night at Wembley will never be forgotten, including the mercurial winger George Best and all-action midfielder Jack Charlton.

But half of England’s Champions League trophies came in six glorious years when no other nation managed to win a single title.

In that period Liverpool grabbed three trophies under Bob Paisley. At the time the Reds had a thrilling brand of attacking football, and forwards such as Kevin Keegan and Kenny Dalglish were the best of their generation.

What was also special was how they kept regenerating: When legendary defender Tommy Smith moved on, Alan Hansen picked up the mantle.

As Kenny Dalglish got older, Ian Rush came through. And when the manager Bob Paisley retired, Joe Fagan stepped in and led them to another trophy in 1984.

In between, the forthright and non-nonsense Brian Clough did something equally amazing with Nottingham Forest, which had never been a big club.

On a small budget he led Forest to back-to-back wins in ‘79 and ‘80. What’s even more astounding is that he did it without stars, and while selling important players on.

Names like Ian Bowyer and Garry Birtles may not be familiar to everyone, but Viv Anderson was a fine defender and Trevor Francis was the one of the finest example of a traditional English centre-forward.

Then came the ban, and it took a long time for English football to regain its standing, even if successes have been a bit more sporadic since the 80s.

The breakthrough finally came at the Camp Nou in 1999, when Alex Ferguson’s Manchester United scored last-gasp goals to defeat Bayern Munich and wrap up an historic treble.

The evergreen Paul Scholes and Ryan Giggs were on hand nine years later to defeat Chelsea on penalties in 2008.

Liverpool, inspired by Steven Gerrard, completed an unforgettable comeback against AC Milan in 2005, after going in three-down at half-time.

And finally, Chelsea defended their way to their first ever Champions League trophy in 2012, drawing on the experience of Lampard and Drogba to get past Bayern on penalties.

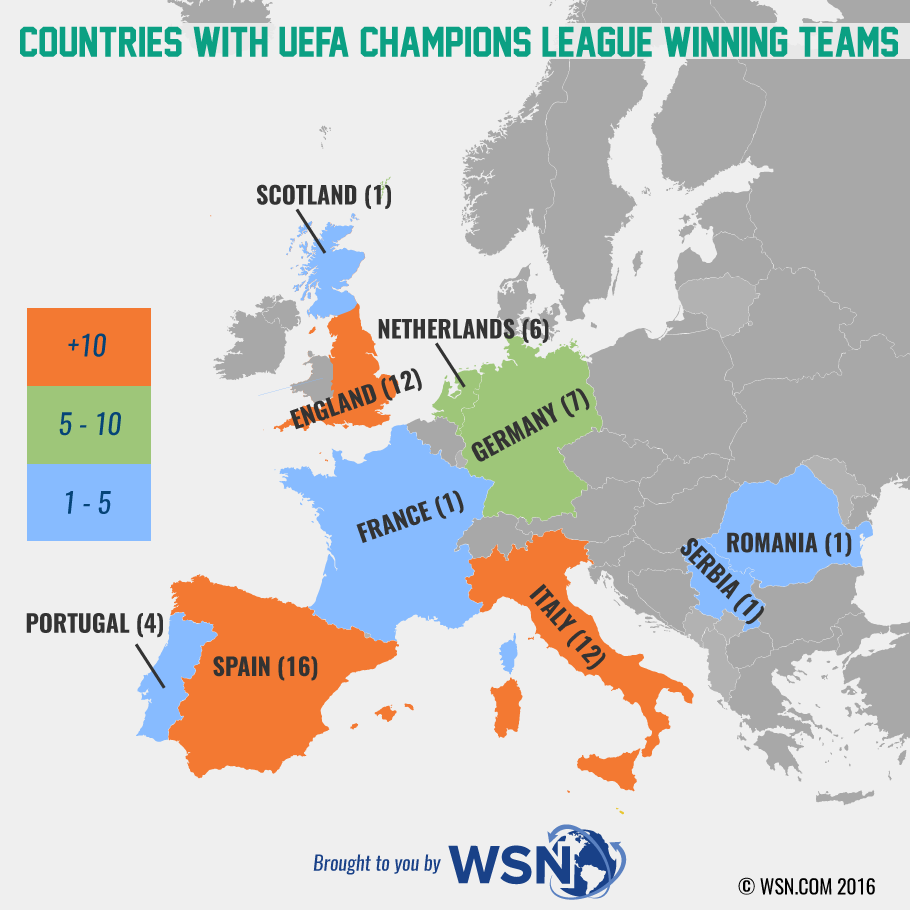

Until 2006 the rest of the Europe was keeping up with Spain for European titles, and England and Italy were even ahead.

But since then Real Madrid and Barcelona have left everyone else in their dust, claiming six of the last eleven titles.

But the foundation for their lead came in the earliest years of the tournament, when Real Madrid won the first five editions, between 1956 and 1960.

It may have been a very different time, but you can’t argue with the attacking talent in those sides, with Alfredo Di Stéfano, Paco Gento, Raymond Kopa and Ferenc Puskás considered among the greatest players of all time.

Di Stéfano had a Cruyff or Beckenbauer-style ability to cover a couple of positions at once, while Puskás’ left-boot was a wand, and he could score from distance given the smallest opening.

These two were long gone in ‘66 when Real Madrid won again, but the left-winger Gento was still around to work his magic.

There’s a big gap between the 1960s and the ‘90s, and the man responsible for putting Spanish football back on the European was Johan Cruyff, this time as a coach.

He set the template that is still bringing success for Barcelona, and won their first Champions League with an elegant and fondly-remembered team in 1992.

Guardiola was the heartbeat, Laudrup was the provider and Bulgarian forward Hristo Stoichkov did the damage.

They triumphed against Sampdoria at Wembley with a free-kick goal in extra time by Ronald Koeman. They would reach the final again two years later, but be upset by Capello’s Milan.

Real Madrid were next to make their mark, beating Juventus in 1998 with a cosmopolitan team boasting Seedorf, Roberto Carlos and Redondo, but anchored by the indomitable centre-half Fernando Hierro.

Then came a period of huge investment by Florentino Pérez, which brought in players like Luis Figo and Zinedine Zidane, and helped claim two more crowns, in 2000 and 2002.

The latter was won by a goal for the ages by Zinedine Zidane when he dispatched a perfect left-foot volley past Hans-Jörg Butt in the Bayer Leverkusen goal.

In the last ten years it’s almost become a two-way fight between Real Madrid and Barcelona for the cup.

Rijkaard led Barcelona to glory in 2006 with a comeback win against ten-man Arsenal, and then Pep Guardiola won it twice, in 2009 and 2011.

At a time when most club teams were becoming a mix of nationalities, Guardiola’s successes came with a nucleus of Catalan and Spanish players. And Messi of course!

Both of those finals were against Alex Ferguson’s Manchester United, and Lionel Messi had a hand in both victories.

Since 2014 no other countries have had a chance. Ancelotti clinched it against Atlético Madrid, and then Luis Enrique’s Barcelona won comfortably against Juventus in Berlin.

And finally, last season Real Madrid, now under Zidane, needed penalties to defeat Atlético. Sergio Ramos’ goal was cancelled out by Carrasco, But after Juanfran missed his spot-kick Cristiano Ronaldo sealed an eleventh Champions League win for Real Madrid.

That’s five more than any other club in Europe.

Does all this make you feel a bit nostalgic? One thing you’ll notice is that until the 2000s footballing talent was more diffuse, and, many great teams would be filled with players from the club’s home nation.

This is definitely a thing of the past, which is one of the reasons it’s tough to imagine any nation outside the big European leagues winning the competition in the future. There just no room for the little guys any more!

At the same time, you have to say that standard has never been higher. Superclubs like Real Madrid, Bayern Munich and Barcelona are have some of the best players in the world in every position.

We support responsible gambling. Gambling can be addictive, please play responsibly. If you need help, call

1-800-Gambler.

WSN.com is managed by Gentoo Media. Unless declared otherwise, all of the visible content on this site, such

as texts and images, including the brand name and logo, belongs to Innovation Labs Limited (a Gentoo Media

company) - Company Registration Number C44130, VAT ID: MT18874732, @GIG Beach Triq id-Dragunara, St.

Julians, STJ3148, Malta.

Advertising Disclosure: WSN.com contains links to partner websites. When a visitor to our website clicks on

one of these links and makes a purchase at a partner site, World Sports Network is paid a commission.

Copyright © 2025